OTTAWAÔÇöOn paper, she seems to be exactly what the Canadian military needs. An enthusiastic would-be recruit, married to a current soldier, and already living on the Canadian forces’ base at Petawawa.

But it has been months, she said, and she hasn’t heard back on even the first step of her application ÔÇö despite a number of failed attempts to wrangle information from a recruitment call centre. Added to this was the discovery of what she claimed was lead paint on the walls of their army-issued house, and the couple is on the verge of quitting for civilian life.┬á

“I’ve always wanted to be part of the forces and represent our country, especially as a woman,” she said, speaking to the Star on condition she isn’t identified.┬á

“I don’t know if I’m still willing to do it,” she continued. “It’s horrible. It’s messy. It makes you think: is it even worth joining this, if this is what it’s going to be?”

That’s not the type of testimonial the Canadian Armed Forces would like to see as it struggles to overcome a personnel deficit that, as of December,┬áexceeded 15,000 regular and reserve members. Most recent stats, from the 2021-22 fiscal year, show the military┬ádealt with “critical shortfalls” in more than 61 per cent of its occupations ÔÇö up from 17.9 per cent two years earlier and much higher than the target of no more than five per cent.┬á

Yet the dearth of people-power is but one of the challenges confronting the Canadian military in 2024.

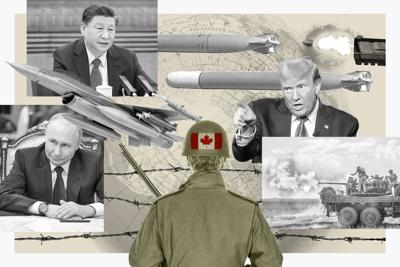

The short-staffed navy, air force and army are still reeling from the cascade of scandals over sexual misconduct allegations within their ranks. Their aging, sometimes Cold War-era equipment is getting more expensive to maintain, and it will take years, and many tens of billions of dollars, before modern warships, planes and Arctic surveillance tech are available. At the same time, there is general agreement ÔÇö including from top Liberal government officials ÔÇö that the world has taken a darker, more dangerous turn in recent years. China’s authoritarian regime has emerged as an adversary of the West, raising fears about the security of Taiwan and the broader Asia-Pacific. War has raged in Europe for two years since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine sparked the greatest conflict on the continent since the Second World War. And over it all looms the possible restoration of Donald Trump to the United States presidency, a prospect that has countries like Canada considering how they can defend themselves with a less reliable U.S. ally.┬á

Taken together, the situation has some lamenting that ÔÇö without a serious infusion of cash and attention from the government ÔÇö the Canadian military could fail to meaningfully contribute as a strong ally in this emerging, more unpredictable world.┬á

ÔÇťWe’re not ready at all. We’re not ready in terms of people. We’re not ready in terms of military capabilities. And, as a result, we’re also losing some of our credibility with allies,ÔÇŁ said Kerry Buck, a former top-ranking official at Global Affairs who was CanadaÔÇÖs ambassador to NATO from 2015 to 2019.

In a written statement, a spokesperson for the Canadian forces said the world is “in a new era of volatility” that is increasing demands on the military, including to respond to climate-related emergencies in Canada. The forces deployed members to natural disasters across Canada for 131 straight days last year.┬á┬á

To respond to this, the federal government has been drafting what it calls a ÔÇťDefence Policy Review.ÔÇŁ In plain English, this will be the blueprint for how Ottawa is rethinking CanadaÔÇÖs place as a military power in a changing world with what the government has a “broader spectrum of threats” amid strains to the CAF.┬á

ItÔÇÖs also taking a long time. Almost two years have passed since the exercise was announced. Bill Blair, Canada’s defence minister, will only hint that itÔÇÖs still coming, possibly before JuneÔÇÖs NATO summit in Washington, D.C.

ÔÇťIt doesn’t seem to look like the government is treating it with any degree of urgency,ÔÇŁ said Guy Thibault, a retired lieutenant-general who spent 38 years in the Canadian military.

ÔÇťBy all objective measures, the Canadian Forces and Department of National Defence don’t have anywhere near the amount of funding and resources it needs,” he said.┬á

Blair was not available for an interview this week, his office said. But the Liberal governmentÔÇÖs response to such criticism┬áhas so far been twofold: Blair and other officials agree Canada must ÔÇťdo more,ÔÇŁ and pledge some future action will fill in the blanks; they also note how defence spending has increased markedly since the Trudeau Liberals took office in 2015.

Which is true.

Under its , unveiled in 2017, the government is pumping billions of dollars towards the military to more than double the Department of National DefenceÔÇÖs annual budget to almost $40 billion by 2026. Much of that new money is going toward the existing strategy to build new ships for the navy, and to replace aging Cold War-era airplanes, including through the up to $70-billion purchase of 88 F-35 fighter jets, a model the Liberals initially rejected as too expensive, and the to replace maritime patrol planes that have been used for more than 40 years.┬á

On top of that, in June 2022, the government pledged $38.6 billion over 20 years to contribute to the ÔÇťÔÇŁ of NORAD, the radar and aerospace partnership with the U.S. that helps defend North America.

Ottawa has also $2.4 billion in military aid to Kyiv since Russia invaded Ukraine two years ago, having donated military hardware like air defence missiles, Leopard battle tanks, and armoured vehicles. And the Canadian Armed Forces is leading the NATO ÔÇťbattle groupÔÇŁ stationed in Latvia, with plans to spend hundreds of millions on new gear┬áand increase its troop commitment to up to 2,200 from the current 1,000.

And it’s trying to wrestle down the personnel shortage, with plans to actually increase the number of “fully trained” forces members. The military has┬á dress requirements and to permanent residents ÔÇö┬áthough, as the CBC first reported this week, the process has proven slow. Just 77 permanent residents enrolled in the CAF between November 2022 and November 2023, out of a pool of more than 21,000 applicants. A spokesperson for Blair, Diana Ebadi, said the minister wants the military to make changes to speed things up, including through “modernizing” medical requirements. Noting how the military also has a plan to prioritize staffing recruitment centres and training schools, Ebadi said the navy is also trying to attract people with a one-year trial program for people to see if they like serving in Canada’s maritime fleet.┬á

In its statement to the Star, the military said labour shortages are affecting the Canadian forces much like private businesses, and that the COVID-19 pandemic made existing personnel shortfalls worse by slowing training and recruitment.

Yet critics say problems abound. Military donations to Ukraine have not been replaced, and there is still no public plan to do so, said David Perry, a defence policy expert and president of the Canadian Global Affairs Institute. That leaves the CAF with a shortage, particularly in artillery munitions. Meanwhile, NORAD improvements wonÔÇÖt be ready for years, much like many of the new planes and ships, forcing the military to rely on equipment that keeps getting older and more expensive to maintain.

Combined with the personnel shortage, the military’s “readiness” statistics have taken a hit. As outlined in the most recent for national defence, 43 per cent of the air forceÔÇÖs fleet was able to ÔÇťmeet training and readiness requirementsÔÇŁ in 2021-22. Just 54 per cent of the navyÔÇÖs key fleets were deemed ready that year, while under 66 per cent of key land fleet equipment ÔÇö tanks, armoured vehicles and the like ÔÇö met these readiness requirements. ┬á

Perry called the shortfalls ÔÇťpretty alarming,ÔÇŁ and blamed policymakersÔÇÖ habit of ÔÇťdoing the equivalent of hoardingÔÇŁ with military hardware.

The navy, for example, has flagged how growing maintenance costs for old ships is ÔÇťputting significant pressureÔÇŁ on its budget, according to a written response to an opposition question tabled in Parliament last month. The response said the navyÔÇÖs fleet of ÔÇťHalifax-classÔÇŁ frigates is already beyond its expected lifespan of 27 to 35 years, and that the fleet wonÔÇÖt be fully replaced with newer ships until between the ÔÇťearly 2030sÔÇŁ and 2050. According to the CAF, overall military spending on the “sustainment” of existing equipment jumped from almost $2.5 billion in 2016 to more than $3.6 billion last year.┬á

Yet even when money is put toward new gear, such as the slew of new planes for the air force, it takes years and a heavy organizational lift to get ready, explained Andr├ę Deschamps, a retired lieutenant-general who was commander of the Canadian Air Force from 2009 to 2012. New generations of airplanes require new hangars, upgraded digital support systems, fresh personnel training and more, he said. But with recruitment issues exacerbated by the pandemic, Deschamps said the military system is overloaded.

“All this change is happening at the worst possible time,” he said. “You’re down to the bones and muscles.”┬á

And there’s pressure to do more. Last April, a group of high-profile figures┬áÔÇö including former Supreme Court Justice Beverley McLachlan, retired top-ranking military figures, senators, and former federal cabinet ministers ÔÇö wrote an open letter, urging the government to overcome ÔÇťyears of restraint, cost cutting, downsizing and deferred investmentsÔÇŁ that have ÔÇťatrophiedÔÇŁ CanadaÔÇÖs defence capabilities. The letter referred to the NATO target to spend at least two per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) on defence, something that Canada┬áÔÇö despite Liberal plans to increase military spending ÔÇö still has no plan to attain.

Mindful of this, Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre recently said he would cut ÔÇťwastefulÔÇŁ foreign aid and ÔÇťback-office bureaucracyÔÇŁ to increase military spending toward the two-per-cent goal.

To Buck, the former NATO ambassador, the target isnÔÇÖt the most important metric for contribution to the alliance, at least in a practical sense. While Canada ranked 25th┬áin NATO for defence spending as a share of GDP last year ÔÇö at 1.38 per cent, according to an by the alliance ÔÇö it jumped to seventh when looking at raw dollars devoted to the military.

But the target is a lot more important politically, Buck said. ÔÇťIt’s used as a political cudgel, in a way ÔÇö particularly by the U.S.,ÔÇŁ┬á she said. ÔÇťIt’s a measure of how seriously you take your defence commitments. And that’s the problem.ÔÇŁ

BuckÔÇÖs advice to government is to draft a spending plan that at least shows ÔÇťa path to two per centÔÇŁ to ÔÇťhelp manage that political hit we take over and over again.ÔÇŁ┬á

Taking such a hit could bring serious consequences. Pointing to arrangements like AUKUS, the security partnership between the U.S., Australia and United Kingdom, Buck said thereÔÇÖs a risk Canada gets left out of important forums in regions that are becoming a larger foreign policy focus, such as the Indo-Pacific. ÔÇťEither CanadaÔÇÖs not invited, or we have to try and claw our way into the group after the fact, so weÔÇÖre not at the table when decisions are made,ÔÇŁ she said.

A bad reputation in security circles could also mean having to rely on allies for help, and potentially make it harder to ask for help ourselves, she said.

The bottom line is that all these issues, from personnel to aging gear to satisfying the NATO spending demands, require money ÔÇö something the government doesnÔÇÖt have much of at the moment, if its gestures toward fiscal restraint can be believed. The Liberals are already looking to shave down public spending by $15.4 billion over the next five years, including savings at the defence department. According to the Business Council of Canada, those cuts might have to quadruple┬áÔÇö or taxes will need to be raised┬áÔÇö if the government stays true to the budget deficit limits it announced last fall.

There are also competing priorities for whatever extra spending is available, as the Liberals wage political war with the opposition over rising costs and CanadaÔÇÖs housing crunch.

But, as Thibault sees it, this new era of global tension simply requires more from the Canadian military.

ÔÇťThe world wonÔÇÖt wait for us,ÔÇŁ he said. ÔÇťWe, collectively as Canadians, have a role to play, a burden to share. And shame on us if we don’t step up.ÔÇŁ

Error! Sorry, there was an error processing your request.

There was a problem with the recaptcha. Please try again.

You may unsubscribe at any time. By signing up, you agree to our and . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google and apply.

Want more of the latest from us? Sign up for more at our newsletter page.

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation