TOKYO (AP) ÔÇö It was small news that dropped during a busy sports week in June. A much-hyped track meet in Los Angeles fronted by one of the sportÔÇÖs greats, Michael Johnson, was being canceled.

It marked the second major event pulled off the 2025 calendar in AmericaÔÇÖs second-largest population center — a city once known for its glamorous melding of track and fame — and the news came a mere three years before Los Angeles hosts its first Summer Olympics since 1984.

The lead-up to the LA Games was supposed to be a time to return the sport to the glory days that peaked in ‘84, when Carl Lewis, Edwin Moses and the rest of trackÔÇÖs stars ran and jumped in the Coliseum by day, then hit red carpets and sat with Johnny Carson by night.

But in some ways, the sport feels more divided and less organized than itÔÇÖs ever been ÔÇô bogged down by the seeming collapse of Johnson’s much-hyped track circuit, a U.S. media deal that makes the sport harder to find and top stars like Noah Lyles, ShaÔÇÖCarri Richardson, Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone and an ever-churning cycle of Jamaican sprinters who donÔÇÖt line up against each other enough.

It came to a tipping point when the cancellations of two meets set for UCLAÔÇÖs Drake Stadium ÔÇô a U.S. Grand Prix event and JohnsonÔÇÖs Grand Slam Track league — were announced within a few weeks.

ÔÇťItÔÇÖs one of the odd situations for a sport that has such an incredible history and legacy, an incredible athlete base,ÔÇŁ said Casey Wasserman, the president of the LA organizing committee. ÔÇťItÔÇÖs an odd thing that there isnÔÇÖt a great track meet here.ÔÇŁ

Momentum from Paris didn’t last a year

The buzz was palpable as track and field closed down the Paris Olympics.

There was drama over each of the 10 days of action bookended by in the menÔÇÖs 100 and distance star Sifan Hassan elbowing her way to victory in the to capture her third medal of the Games.

ÔÇťThis is our moment,ÔÇŁ World Athletics President Sebastian Coe declared at the time. ÔÇťWe canÔÇÖt sort of allow this to glidepath gently into anything other than a really successful 2028.ÔÇŁ

What happened over the ensuing 12 months has been anything but gentle.

Most of the attention revolved around Grand Slam Track, the multimillion-dollar start-up brought to life by Johnson who, like so many in the sportÔÇÖs hierarchy, tired of seeing the athletes fade into the background once the Olympic torch went out.

He offered big money and promised head-on-head racing. McLaughlin-Levrone and Olympic gold medalist Gabby Thomas signed on. Lyles and Richardson did not.

That league promised four meets, but problems began after the opener in Jamaica that failed to wow potential investors. A few weeks before the season-ending LA meet was scheduled came news that virtually none of the runners who signed up were getting paid.

ÔÇťUnderstandably, this has led to frustration, disappointment and inconvenience to our athletes,ÔÇŁ Johnson wrote on the last month, responding to reports that the $30 million in seed money he touted turned out to be more like $13 million. ÔÇťI know this damages trust.ÔÇŁ

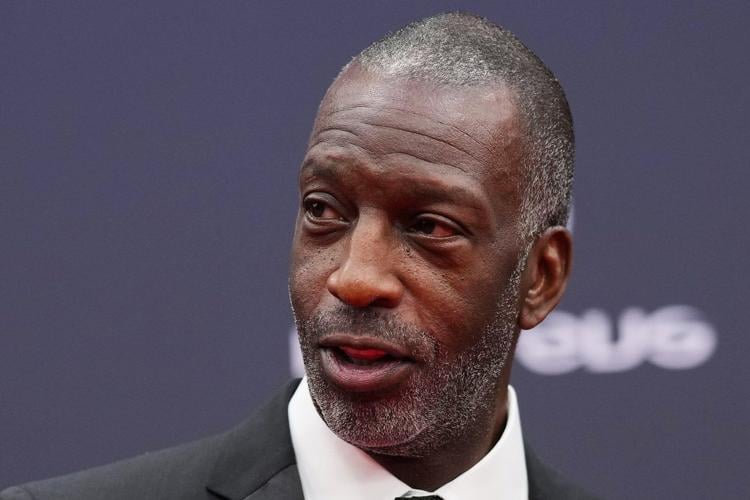

Moses, the legendary hurdler who spent his career advocating for track stars to get paid, said he heard complaints from every corner.

ÔÇťIt just shakes the pillars of track and field, when an athlete canÔÇÖt get paid and theyÔÇÖve already competed,” he said.

Amid all this, the venerable Diamond League stayed the course, offering 16 meets, mostly across Europe but with a few spread in Asia and one in the U.S. Only once over those 16 meets did the three biggest names in sprinting in either men’s or women’s competition line up in the same 100-meter race.

ÔÇťThere’s a lot of different factors,ÔÇŁ McLaughlin-Levrone said. ÔÇťHaving exciting races is part of it, but if nobody can see those races, that doesn’t really help anybody.ÔÇŁ

That’s a reference to the Diamond League’s long-term association with NBCÔÇÖs streaming arm, Peacock, not being renewed after 2024. Instead the U.S. rights went to FloTrack, the track-specific website that charges somewhere between 5% and over 100% more than Peacock, depending on the subscription.

Athletes were among the many scratching heads about that arrangement.

ÔÇťThis might be the worst news IÔÇÖve heard from the diamond league since ... ever,ÔÇŁ Thomas posted on social media.

ÔÇťI think thatÔÇÖs horrible for the sport,ÔÇŁ Moses said.

A potential NFL-sprint rivalry gets stuck in the blocks

In what might be the most telling sign of where the sport stands, at least in the United States, it was the latest in a long history of NFL trash talk ÔÇö all those receivers swear they could beat the fastest sprinters in the world ÔÇö that generated more hype than anything.

Lyles and Miami Dolphins receiver Tyreek Hill traded insults and challenges back and forth about who could beat who. They talked about setting up an exhibition ÔÇô the sort of event that, if stood up and promoted properly, couldÔÇÖve been the kind of one-off that streamers live for in the search for buzzy sports content.

But , as an injury to Lyles and the onset of NFL minicamps and training camps approached.

Just as well, said Moses, who has seen it all over 40-plus years watching the sport.

ÔÇťThe average (receiver), they’d have a hard time beating the top women’s sprinters in a 100 or a 200,ÔÇŁ he said.

World championships put the sport on stage again

The sportÔÇÖs next time to shine starts Saturday at , when track returns to Tokyo, the site of the 2021 Olympic meet that was held in front of mostly empty stands because of the COVID pandemic.

The championships will offer tales of second chances ÔÇô for the city itself, for Lyles, who finished third there , and for Richardson, who missed those Games because of the now-immortalized doping positive for marijuana.

In a year, World Athletics will try to keep track on the map by kicking off a new event ÔÇô the World Athletics Ultimate Championship ÔÇô a three-day meet in Budapest that will invite only the very best to compete in a finals-only format for $150,000 first prizes.

By then, more will be known about a lot: whether JohnsonÔÇÖs league will make it; whether a women’s-only series called Athlos, which is fronted by Reddit founder Alexis Ohanian, could serve as a fitting substitute; who the upcoming stars might be for LA; and whether track ÔÇö bound to be a huge draw in LA no matter what ÔÇö will be anything more than a passing thought once those Olympics are over.

ÔÇťYou still have some of the most extraordinary, talented athletes and a track and field team thatÔÇÖs one for the ages,ÔÇŁ Coe recently said of the Americans. ÔÇťThey canÔÇÖt walk around Zurich without being bombarded outside hotels and on the street, and theyÔÇÖre still walking around in relative anonymity in their own hometowns. ThatÔÇÖs always been the disconnect.ÔÇŁ

___

AP Summer Olympics:

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation