It was once a familiar part of Brantford, Ont. — a respectable-looking institution that people would pass by with no suspicion about what was going on inside. Which was, often, cruelty. The new book “Behind the Bricks: The Life and Times of the Mohawk Institute, Canada’s Longest-Running Residential School” gathers bleak accounts of life inside those walls for the Indigenous students: loneliness, sexual abuse, violence and more, over decades, ending when the institute closed in 1970. This portion edited by Richard W. Hill Sr. collects former students’ recollections of school discipline, and even abuses between students, under the heading, “On Being Punished.”

��“They had one little room — it had just had room to crawl in and go in the bed if you done anything wrong. That’s how he’d punish you — he’d make you go in that room. No light — shut the door and lock it from the outside. You couldn’t get out of there and you had to stay in there so many hours.”����

—��Martha Hill, Grand River, (attended 1912-18)

Lorna and her sister Salli entered the school in 1940. Lorna recalled a girl who was caught out of bounds in the dorm because she was having her period and wanted privacy. The girl was nineteen years old, but still in Grade 5. Principal Horace Snell sent for her to come to his office, but she refused. The principal then went to the girls’ playroom and strapped the teenager in front of the others. The girl was beaten so severely that she had an epileptic seizure. When the other girls intervened because the principal kept strapping her, Snell became enraged and began shoving and knocking the girls down. When he recovered the strap, he began to beat all of the girls. The principal’s wife came down and threatened the girls that if they told anyone what took place, they would “get worse.” The other girls asked the girl, who was covered with welts on her back, head, face, legs, and rear end, why she refused to go with Snell. She replied, “I don’t know, but I didn’t want to get raped.”

Frank Hill��(1945-7) recalled how older boys suspended a little boy from the hot overhead pipes, just to see how long he could hang there. Some boys would hang themselves with their towels from those same pipes until they passed out. Boys would steal potatoes, cabbage, and carrots from the root cellar. Boys would convince the kitchen help to become their girlfriends so they could get extra food. On a sad note, Frank, who worked in the barn, found a collie that he called Lassie. The dog would help him round up the cows. One of the staff members, always trying to break the boy’s spirit, shot and killed the dog out of spite.

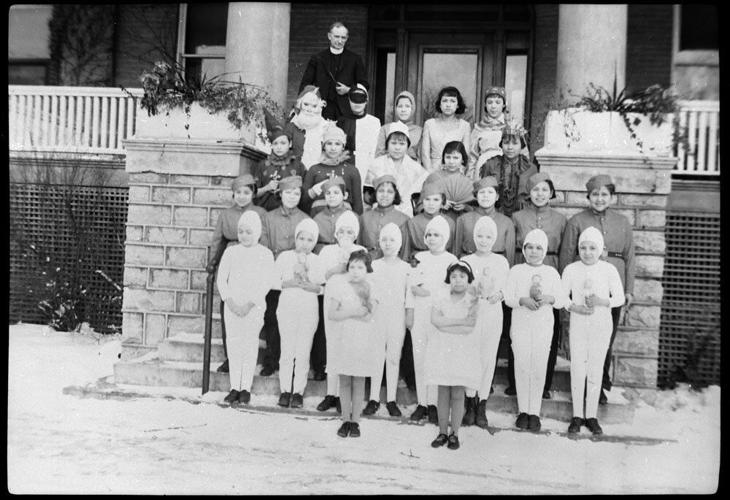

A Mohawk Institute survivor Lonnie Johnson, 82, stands in front of the former school in 2021.

Barry Gray The Hamilton SpectatoVera Styres, attended twice, first in 1942-3 and again in 1946-7. Vera recalled that captured runaways were punished by the other students by crawling through a lineup in which each student would give them a whack on their behind. The girls wore handmade striped work aprons and denim tunics. Button-up underwear was made of stiff, itchy cotton from recycled sugar bags or flour sacks. Vera said she was punished if she got sick, and that the nurse would not treat the students. She got so sick and skinny that her mother, who visited once a month, marched up to Principal Zimmerman and punched him right in the face for letting her daughter get in such a condition. In response, he began to force feed Vera.

“I ran away once and when I got back there I really got the strap — right to (forearm) — cut my wrist open. I seen a lot of them like that, getting the strap, and they wouldn’t even cry. They punished us for practically nothing … I couldn’t even go and talk to my sister. . . . I’d get the strap just for talking to my sister.”��—��Emmert General, Grand River, 1932(?)-9(?)

Peggy Hill��(1955-7) recalled her life behind the bricks as a series of fights with other students, or punishments from the principal. “Our only crime was being poor — our parents couldn’t feed us the way the Indian agent thought we should be fed.” Two runaways got caught and were strapped in front of all the students. Peggy got caught stealing food to sneak to her brothers, who were also in the school. For that she got strapped. Once a teacher knitted her a sweater, but a jealous student cut a big hole out of the back. Peggy got blamed and was strapped.

��Blanche Hill-Easton (1943), tells of a time when a teacher who she thought was a friend beat her and damaged her back when she was 10 years old: “I was in the sewing room when the teacher got really upset with me because I was crying, and the more she told me to not cry, the harder I cried — and she grabbed me by the hair, and grabbed me by the back, and we were on the bench, and she pulled me right over onto the floor, and then started beating me with the strap. They had a big strap, it looked like those straps that they do with the razors, the men’s razors straps. But it had a point on it, and when she hit me with that, she hit me in the middle. Struck me from behind and wrapped around the front of my head and everything, but she kept right on beating me. I hit my head, and hit my shoulder on this side, and I passed out. To this day, I still have that problem, I have a fused vertebrae in the back, and now this whole side has gone.”

Jo-Bear Curley��was a student twice, from 1955 to 1958 and from 1962 to 1964. She used to sneak out of her dorm to watch television in the girl’s playroom in the basement. She was punished for stealing apples and getting caught kissing her boyfriend. For her punishment, she had to scrub the floor with a toothbrush. Jo-Bear recalled some darker moments. The girls would challenge each other to choke themselves with the scarves that they would wear on their heads. She choked herself until she blacked out. One girl was being punished by an Indigenous staff person and was beat so badly with a strap that her arms and shoulders turned black and blue, yet she would not cry out in pain.

��I interviewed Pat Hill, an 82-year-old survivor who lives in Buffalo, New York. She attended from 1946 to 1950. Pat had worked at cleaning the principal’s apartment, which was next to the girls’ dorm. She also had to serve food in the officers’ dining room in the basement. She recalled that Principal Zimmerman was brutal, and he beat her repeatedly, for which she confesses that she never knew why. “He had no mercy on anybody … I often wonder, after I left, that whatever possessed him — how he could do it and get away with it, but he did … He knew you couldn’t go anywhere, even if you told somebody. Didn’t make any difference.”��Once she was locked in the third-floor attic for a few days as a punishment. When Zimmerman tried to punish her, he insisted that she drop her pants so he could strap her bare bottom: “I used to have to fight with him, cause he wanted me to take my … dresses, he wanted me to take it down.”��Pat found it ironic that Zimmerman would always preach to the students about the sins of sex at the Mohawk Chapel every Sunday, yet his own conduct made that seem hypocritical. Pat ran away but was caught by Zimmerman. “I had had so many beatings, I wanted to get out of there. You know when you’re a kid and somebody is beating you all the time, you try to get away as far as you can.”��One night a couple dozen girls ran away. Pat recalled how the girls used to scale the outside of the building, at the corners with small ledges in the brickwork, to sneak in and out of the second-floor dorm. Inside, there was constant fighting. Her younger sister was always fighting, and sometimes she would have to jump in to defend her. When asked what she would say to Zimmerman after all these years, she replied as follows: “I don’t think I’d ever talk to him. He ruined my life. He made me a hateful person when I was younger, and as you got older, it stayed with you. Never goes away. I never forgot those years. But like I said, I’m a survivor.”

“Behind the Bricks: The Life and Times of the Mohawk Institute, Canada’s Longest-Running Residential School”

University of Calgary Press

402 pages

$42.99��

Courtesy of Serif“When we little kids wet our bed, we’d really get it. We had to wear the sheet like a diaper during lunch, and then had to wash the sheets. They used to march us into breakfast with these sheets around us.”��—��R. Gary Miller, Tyendinaga Mohawk, 1953-64

Beverly Bomberry (1943-6),��Mohawk, now Beverly Albrecht, recalled her worst memory: “We were running around the bunk beds and we got caught (by the house mother). And so, we got sent downstairs, and they had the playroom, and then there was a little office, and in the office was lockers, and they put us in the lockers. I was screaming and screaming to get out … I don’t even know how long I was in there, but to me it seemed like a long time because I’m young. And then I realized, oh if I stop screaming, they’ll let me go. But to this day, I can’t leave a door locked. Like, in my bedroom, I gotta have it open, because I always think I’m trapped. I know I’m not, but that’s just in my mind.”

Marguerite Beaver��(1940-8) recalled that a female student had a baby that was rumoured to have been fathered by one of the teachers. While Marguerite suffered no sexual abuse, likely because her mother, also a graduate of the school, worked for the Crown attorney, she was caught smoking and had her hair cut short as punishment. She also recalls getting the strap several times for offences such as running away: “The strap was about a foot long and about four inches wide, and they hit you with that and naturally it stings for the first two or three times and after that it goes numb.”

From��“Behind the Bricks: The Life and Times of the Mohawk Institute, Canada’s Longest-Running Residential School,”��© 2025. Reproduced with the permission of��University of Calgary Press.

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation