On a warm evening in September 2023, a car pulled up to the Lighthouse Inn, a rundown roadside motel set behind a pub in the city of London, Ontario. The teenager in the passenger seat had been crying since her mother left her in the lobby of the childrenÔÇÖs aid society office that afternoon, but now she looked numb.

Jade was 14, with bright eyes and a sun-kissed complexion. She loved riding roller coasters, singing karaoke and eating popcorn with apple slices. At her best, she radiated spunk and confidence. But she was also a challenging kid who had been dealt a difficult life. Diagnosed with several mental health conditions including post-traumatic stress disorder, she struggled to manage big feelings and impulses that sometimes led to violence.

A child protection worker guided Jade into the motel and down the hall to a room that faced the parking lot. It had a musty smell, worn carpets, and a yellow outline on the wall where a second bed had been.

The night before, Jade had slept in the cosy lower nook of her bunk bed, at her birth motherÔÇÖs house in the country. Now she carried just two small bags of clothes. Many of the things that would have brought her comfort had been left behind, including Moo-Moo, the stuffed brown cow her father had given her when she was adopted as a toddler.

At the motel, Jade was left in the care of strangers, support workers from a private agency who were paid hourly wages to monitor children like her 24/7, and who stayed in a room across the hall. She had no one to cook her dinner. No family to hug her goodnight. No one she trusted to talk her through the events that had pushed her adoptive parents, and then her birth mother, to turn to CAS.

It would be the last and most difficult year of her life.

In Ontario, childrenÔÇÖs aid societies, which are overseen by the provincial government, are bound by law to take children who come into their care to a ÔÇťplace of safety.ÔÇŁ But finding safe homes for the provinceÔÇÖs most at-risk children has become nearly impossible, forcing child welfare agencies to take desperate measures.

Over four years, childrenÔÇÖs aid societies have housed hundreds of vulnerable kids, including many with mental health conditions and high-risk behaviours, in motels, Airbnbs, office buildings and other unlicensed settings. The province and CAS leaders are locked in a battle over who is ultimately responsible. Government officials say itÔÇÖs up to child welfare agencies to find safe placements. But CAS leaders say they have no other options amid a provincewide shortage of intensive treatment and residential care that the government has failed to address.

In London, housing kids in hotels has become so common that child protection workers have given the placements a name: ÔÇťPlan C.ÔÇŁ

Jade would spend the next 13 months being shuffled between budget motels and unlicensed group homes, all while in the care of the Children’s Aid Society of London & Middlesex. She would run away at least seven times, turning up in hospital emergency departments after drug overdoses and a violent assault. She would sleep in homeless encampments and be flagged as a high risk for sex trafficking.

Through it all, provincial officials knew she was at risk. Child welfare agencies are required to alert the government each time a child is harmed, goes missing or has a serious health concern.

During her final year in the care of CAS, Jade received no meaningful treatment for her mental health conditions. Instead, she fell further into crisis.

This story is drawn from more than 100 interviews, court transcripts, emails, CAS documents, leaked memos, and provincial government records obtained through access to information legislation. The records document the last year of JadeÔÇÖs life and the crisis forcing vulnerable children into hotels, and tell the story of a preventable death.

They also illustrate in rare detail the lives of vulnerable children who live in the shadows, in part because OntarioÔÇÖs strict privacy laws prevent them from being identified, even after┬ádeath. To comply with publication bans, the ╔ź╔ź└▓ Star has used middle names, nicknames or initials throughout this story. JadeÔÇÖs adoptive parents and birth mother agreed to interviews because they want her story to be told to protect other children.

Jade knew she was in danger, her family said, and in moments of clarity she wanted to change.

ÔÇťThis year has been crazy, but IÔÇÖm going to be better for you,ÔÇŁ she wrote to her father months before her death.

Her parents, child protection workers and support staff spent months trying to get her help that came days too late.

ÔÇťEverybody was saying the same thing: sheÔÇÖs going to die if this keeps up,ÔÇŁ said one London CAS source, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they arenÔÇÖt authorized to discuss the case. ÔÇťAnd then she did.ÔÇŁ

In the summer of 2010, Mona and Tim got the call theyÔÇÖd been praying for. The childrenÔÇÖs aid society had a 15-month-old girl who needed a home.

Tim remembers meeting Jade for the first time, how she looked at him skeptically and refused to hold his hand, then turned her back, shook her bum and laughed. He drove her to Walmart and told her she could choose a stuffed animal, whatever she wanted. Jade went after the first one she saw, a smiling brown cow with floppy ears that she named Moo-Moo.

Jade’s art.

Married for┬á10 years, Tim, a bartender, and Mona, an account manager for a bank, lived with their three-year-old son in a middle-class suburb in London. They had decided to adopt after complications with MonaÔÇÖs first pregnancy.

Mona and Tim were told little about JadeÔÇÖs history except that she had come from an unstable home, they both said. Born to an 18-year-old mom and apprehended by London CAS at six weeks old, Jade had spent a year in foster care before she was placed for adoption.

Soon after Jade joined their family, Tim had a heart attack and the parentsÔÇÖ marriage grew strained. Tim and Mona divorced when Jade was three, another big adjustment for a child whoÔÇÖd lived through a lot of instability. Jade lived with her mom, who remarried, and saw her father every other weekend.

Jade was a spirited child who loved the thrill of new experiences and wanted everyone in a room to be happy. Playful moments from family videos show her bouncing on her backyard trampoline, making slime and singing pop songs in her childhood bedroom, which had magenta walls and a loft bed strung with twinkling lights. At nine, she filmed herself performing JourneyÔÇÖs ÔÇťDonÔÇÖt Stop Believing,ÔÇŁ her tongue stained Ring Pop blue.

From a young age, Jade struggled to regulate her emotions. A kindergarten report card described her as ÔÇťhighly impulsive.ÔÇŁ Mona said she made friends easily, but had trouble keeping them. Daily reports from elementary school paint a picture of an overstimulated child getting rough with classmates. Once, a teacher had to evacuate the classroom after Jade grabbed another student by the shirt. By Grade 1, Mona was getting calls a few times a week to pick up Jade from school, and she eventually had to take a leave of absence from work.

Mona looks over some of the items she has saved to remember Jade, including childhood artwork and her daughterÔÇÖs favourite blanket and toys.

Steve Russell/╔ź╔ź└▓ StarCourt records show that CAS opened a file when Jade was nine due to ÔÇťparent-child conflict,ÔÇŁ the same year her outbursts became more aggressive, according to her mother. Mona said child protection workers and police officers who responded to emergency calls at her home told her that if she tried to restrain Jade or defend herself, she could be criminally charged. CAS advised Mona to install a lock on her bedroom door and phone 911 if Jade became violent. Over the next two years, Mona called emergency services eight times, she said.

Any efforts Mona made to find help seemed to go nowhere. Waitlists for therapy and programs were months or years long. The family was offered phone numbers for crisis hotlines, rather than support to prevent a crisis. Mona suspected Jade may have fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), but said a doctor dismissed her concerns and suggested the problem was her parenting.

The family conflict escalated during the pandemic. ÔÇťIt felt like our household was falling apart,ÔÇŁ Mona said. In 2021, Jade, then 11, removed the screen from her second-floor bedroom window and threatened to jump, Mona said. Paramedics took Jade to the local childrenÔÇÖs hospital, where she was admitted to the mental health unit.

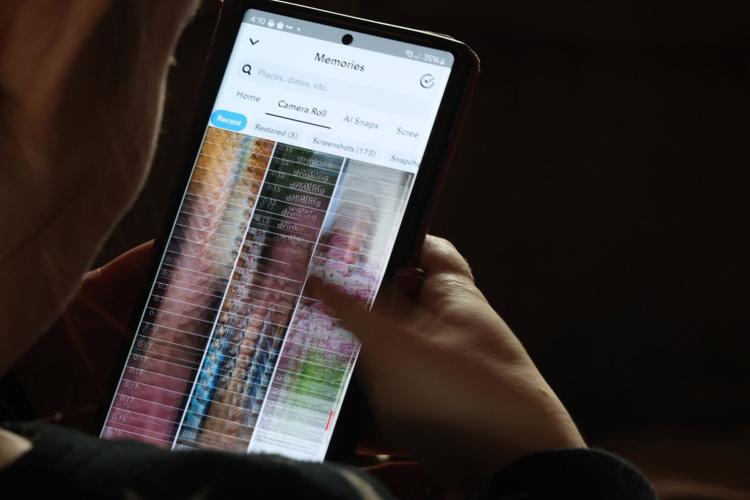

After the crisis, Jade moved in with Tim. She and her father had always enjoyed a chummy camaraderie. On their weekends together, they would go for long drives in TimÔÇÖs Jeep with the windows rolled down, singing Meat LoafÔÇÖs ÔÇťBat out of Hell.ÔÇŁ But now Jade refused to go to school. Tim would arrive home from work to find her in bed, scrolling on her smartphone. She became obsessed with TikTok and Snapchat. When Tim cut off her internet access, Jade smashed his dishes. One day, she found his hunting knife and held it to her belly, threatening, again, to kill herself. Police took her to the hospital. She stayed a few days, and then doctors discharged her after she said she wouldnÔÇÖt hurt herself again, Tim said.

Jade and her father Tim in shadow on a walk in the park in 2021. She was 12.

Tim felt he didnÔÇÖt have the coping skills to handle JadeÔÇÖs outbursts. He worried that in attempting to stop her from hurting him or herself, he would end up hurting her.

In early 2022, Tim and Mona signed over temporary custody to the London CAS. Though they would remain in JadeÔÇÖs life, childrenÔÇÖs aid was now responsible for her care.

It was a painful decision, and one that more families are being forced to make.

For nearly five years, child welfare agencies across the province have warned the Ontario government of the rising problem, according to documents reviewed by the Star.

Over multiple letters sent in 2023 to ministers responsible for health and childrenÔÇÖs welfare, leaders at the London CAS said parents are being forced to take the ÔÇťextraordinary measureÔÇŁ of relinquishing care because they can no longer manage their childÔÇÖs behaviour, fear for their personal safety, or wrongly believe CAS has better access to treatment.

The London CAS leaders warned the government they were now facing ÔÇťa critical inabilityÔÇŁ to access intensive mental health support for a growing number of children with high needs.

Jade was 12 when she moved into her first group home, in March 2022. Within weeks, she was smoking marijuana, skipping school and running away, behaviour that eventually got her kicked out of the home, her parents said. The London youth residence was the first of at least 10 placements she would have over the next two and a half years, according to CAS records shared by her family.

That May, London CAS found Jade a bed at a treatment centre in southeastern Ontario. It was a four-hour drive from home, but Jade would have counselling, school and distance from the unhealthy friendships sheÔÇÖd made in London. The centre even had an animal therapy program, perfect for a kid who loved dogs and horses.

Before she left London, Jade had reunited with her biological mother, Nicole, who Tim had tracked down, hoping that Jade might overcome her feelings of rejection if she learned more about her early life. Nicole was 31 and lived in a rural community outside of London. She had spent a decade addicted to crystal meth and living on the streets after losing Jade, but had since gotten clean and started to rebuild her life. She was eager to finally be a mom.

During JadeÔÇÖs year at the treatment centre she visited Nicole on weekends. They had fun together, playing Ouija board, cracking up over Snapchat filters and dragging mattresses into the living room for movie nights. It was decided that once Jade, now 14, completed treatment in the summer of 2023, she would move in with Nicole, which would give her a fresh start for high school.

JadeÔÇÖs parents recall that summer as a hopeful time. The treatment centre had given Jade┬áinsight, coping strategies and stability. She was seeing a therapist and taking medications to treat her mental health conditions. Her family attended her Grade 8 graduation at the centre and Nicole hired a photographer to take pictures of Jade in her cap and gown. Mona planned a family trip to CanadaÔÇÖs Wonderland in August and invited Nicole. They all spent the weekend in the home Jade had grown up in, talking and laughing in the backyard, swimming in the pool and eating barbecued ribs, JadeÔÇÖs favourite.

Mona would remember it later as the last good time they had together.

Two weeks before starting high school in August 2023, Jade moved into the small, two-bedroom house her birth mother rents in a farming community outside London.

Nicole was hopeful, but had some reservations. She was only a few years clean, with her own childhood trauma and mental health conditions, including borderline personality disorder. Nicole and her own mother, who lives nearby and has supported her since she stopped using drugs, said they asked CAS for more time and additional support, including parenting classes, but were told the agency didnÔÇÖt have the resources. Nicole would later say she felt pushed into taking Jade home before she was ready.

At school, Jade was bullied for being in a classroom for students with special learning needs, her mother said. She started skipping class and lashing out at home. When Nicole confronted her, harsh words escalated into a physical altercation. Nicole said Jade smashed her head into a dresser, forcing her to barricade herself in the bathroom and call the police.

Nicole worried that another fight could lead to further violence. And with an extensive criminal record from her years on the streets, she believed any wrong move could land her in jail.

Two weeks after Jade moved in, Nicole and her mother packed some of JadeÔÇÖs clothes into two small bags and picked her up at school. They didnÔÇÖt tell her they were returning her to childrenÔÇÖs aid until they entered the London CAS office. Nicole and her mother later said keeping the plan under wraps was meant to prevent Jade from running away; she had been known to jump out of moving vehicles. But it was a crushing blow to a child who already felt abandoned. JadeÔÇÖs screams echoed through the office hallways and she had to be restrained. CAS staff called a ÔÇťCode Red,ÔÇŁ warning people to keep away from the lobby.

Nicole said she intended JadeÔÇÖs return to CAS to be temporary. She wanted to work on her coping skills and bring Jade back when they were both ready. But Jade didnÔÇÖt see it that way. She refused to speak to Nicole for months.

Jade couldnÔÇÖt live with either of her adoptive parents. Tim didnÔÇÖt have appropriate housing; he was living in a friendÔÇÖs basement apartment. Mona, who had an older son and stepchildren, feared for her familyÔÇÖs safety and the impact an open CAS file could have on custody of the other children. Unable to find Jade a foster home, treatment centre or group home, London CAS turned to its last-resort option: a roadside motel.

The Lighthouse Inn was JadeÔÇÖs home for a month. From her motel room, she posted TikTok videos, often lip-synching rap songs about sadness, drugs and suicide. (ÔÇťMy life is goinÔÇÖ nowhere/I want everyone to know that I donÔÇÖt care.ÔÇŁ) She started missing curfew and wasnÔÇÖt going to school. She refused therapy and quit taking her medications.

One night in October, Jade didnÔÇÖt return to the motel. London police issued a missing persons report that pictured her with a youthful grin, flushed cheeks and tousled, shoulder-length hair. She looked even younger than 14. It was the first of at least seven such alerts issued as Jade fled life in hotels and group homes, and began using hard drugs.

When Jade returned a week later, CAS had a new safety plan. It noted that she had ÔÇťa history of being AWOL,ÔÇŁ past suicidal thoughts and behaviours, and could be ÔÇťextremely aggressiveÔÇŁ toward parents, workers and other youth. Jade was not to have sharp objects. Her medications were to be administered by support workers. Staff were to check on her every 30 minutes, or every 15 if she appeared to be ÔÇťunder the influence.ÔÇŁ Any unapproved absences were to be reported to police immediately because Jade was ÔÇťknown to be engaging with adult men (and) substances.ÔÇŁ She would remain at the hotel.

JadeÔÇÖs case manager, J.G., was a veteran child protection worker who was not easily rattled. Her communications with Tim and Mona are documented in emails the parents shared with the Star.

J.G. began looking into placements at OntarioÔÇÖs three live-in secure treatment centres for youth, which treat kids with serious mental health conditions. These were the only options CAS had for children like Jade, whose high-risk behaviours and refusal to consent to treatment excluded them from scarce live-in programs. But secure treatment is nearly impossible to get into, say parents, child advocates and CAS workers. The waitlists are long and the programs require a court order for involuntary admission.

J.G. submitted applications, but warned Tim, ÔÇťI have been told this process can take months.ÔÇŁ

In late October, CAS moved Jade to another roadside motel outside of London. Her parents and child protection workers agreed they needed to keep Jade out of the city and away from easy access to drugs. Mona visited Jade at the motel and was shocked that CAS had placed her 14-year-old daughter there. It was also being used as a homeless shelter for adults. Chips and cupcakes were spread across a table in JadeÔÇÖs room. She told her mother she had eaten little else but fast food for weeks.

Soon after, Jade went missing while in London for a medical appointment with youth support workers. When Jade ran away, she sometimes stayed with people she called her ÔÇťstreet familyÔÇŁ in homeless encampments, her father said. Other times, she stayed with adult men she described as boyfriends. Nicole feared Jade might be having sex in exchange for drugs. Her CAS worker believed she was at risk of sex trafficking.

In early November, Tim was shocked to learn that childrenÔÇÖs aid was planning to move Jade back to the city. A space had opened up at an unlicensed group home, one of two houses London CAS had rented and staffed with contract workers to accommodate the increasing number of high-needs children coming into care.

Tim shared his concern in an email exchange with JadeÔÇÖs child protection worker. ÔÇťI thought that we were trying to keep [her] out of London,ÔÇŁ he wrote. His daughter was getting pulled deeper into the drug world. A group home or motel in London was only going to make things worse.

J.G. acknowledged that it wasnÔÇÖt ideal. ÔÇťThis is a short-term placement and better than being in a hotel,ÔÇŁ she wrote, adding that while CAS continued to search for an ÔÇťappropriate placement,ÔÇŁ nothing was available.

Tim was angry. ÔÇťI hope they find a place for her before they find her dead in an alley,ÔÇŁ he wrote.

J.G. didnÔÇÖt try to defend the move. ÔÇťI understand your disappointment and frustration with the society (and) the lack of resources available and the inability to keep your daughter safe,ÔÇŁ she replied. She suggested Tim contact his local MPP.

ÔÇťThis may prompt more action by the government,ÔÇŁ J.G. wrote, ÔÇťas they are very aware of the placement crisis for our youth in the community.ÔÇŁ

JadeÔÇÖs father, Tim, said he believes his daughter could have turned things around but was denied the chance.

Steve Russell/╔ź╔ź└▓ StarDuring the year Jade shuttled between hotels, the long-simmering placement crisis was turning into what one CAS leader called a ÔÇťfive-alarm fire.ÔÇŁ

The number of children in emergency placements had nearly tripled in three years, according to the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies (OACAS), an organization that represents child welfare agencies. During a 12-month period ending in March 2024, there were 339 kids and teens living in unlicensed settings, up from 124 two years earlier.

In Ontario, residential services for children and youth, such as group homes, are licensed under provincial regulations. But the government also permits the use of unlicensed placements.

Sometimes, an unlicensed placement may be the best option for a child, such as when a teen with unique developmental needs is placed in a home meant for adults. Increasingly, however, child welfare agencies are making these arrangements out of desperation. In one town in southwestern Ontario last year, child welfare leaders were forced to house a 10-year-old boy in their office for eight months after 98 group homes and live-in treatment centres declined to accept him.

Documents obtained by the Star show at least five warning letters from three different regions to the ministries responsible for health and child welfare, sent between 2022 and 2023.

London CAS had experienced several concerning incidents. In December 2021, a support worker from an outside agency who was supervising a youth in a hotel had been stabbed while trying to break up a party in the childÔÇÖs room. Afterward, the agency moved its youth into the CAS building, but later the fire department stepped in and said they couldnÔÇÖt have kids living in the office.

Child protection workers were also sounding the alarm about being forced to warehouse vulnerable children in motels and Airbnbs. In a union survey of 450 staff from across the province last year, workers stressed the danger of these placements.

ÔÇťI am disgusted and astounded that these living arrangements are even being allowed,ÔÇŁ wrote one worker who had been supervising children in hotels. ÔÇťI am certain that any minister or their staff would not stay at motels/hotels such as these and would likely cause an uproar if THEIR child was ever placed there.ÔÇŁ

On a cold February morning, five months after Jade moved into her first hotel, police found her at a townhouse in London, unconscious from a suspected fentanyl overdose. Jade had run away from the group home sheÔÇÖd been living in. An officer administered Narcan, a medicine that can reverse the drugÔÇÖs deadly effects, and Jade was taken to the hospital by ambulance.

Tim saw some hope in this alarming news: now hospital staff would be forced to get his 14-year-old daughter into a treatment program. But a doctor told J.G. that Jade would be released because she was ÔÇťnot actively suicidal,ÔÇŁ according to a written account of the conversation the CAS worker shared with Tim. Jade had admitted to meth use and said it may have contained fentanyl, but she told doctors she didnÔÇÖt intend to harm herself. Tim saw it differently. ÔÇťShe knew exactly what to say to get out of the hospital,ÔÇŁ he said.

Released, Jade was taken to a Holiday Inn, and then disappeared again. This pattern repeated itself over several months.

In March, Jade spent two weeks at a youth detention centre north of London. She had been arrested for failing to appear in court to answer to criminal charges after threatening a worker at one youth residence, and punching a hole in a wall at a hotel after getting kicked out of her group home.

Nicole keeps photos of Jade on her phone and often looks at them when she misses her daughter.

Steve Russell ╔ź╔ź└▓ StarWhen Tim visited Jade at the jail, she was calm, clear-headed and noticeably drug-free, he recalled. ÔÇťShe wanted to get clean and get her education,ÔÇŁ Tim said. They made plans to go camping together that summer in Algonquin Park. Tim felt strangely at ease when Jade was in jail. ÔÇťAt least she was safe,ÔÇŁ he said.

Jade pleaded guilty and was released on terms that included an order to remain in her home ÔÇô a London hotel ÔÇô except when she was with her youth support workers. Over the next six months, she would run away repeatedly and be arrested more than a dozen times for failing to comply with her release terms, prompting one judge to acknowledge she was caught in a ÔÇťrevolving door.ÔÇŁ

On several occasions J.G. and the workers who supported Jade at the hotel asked the court to hold her, citing concerns for her safety, including drug abuse. In one hearing, a crown lawyer said the court had received reports from JadeÔÇÖs workers suggesting ÔÇťcustody may be helpful to separate this individual from drugs and improve her well-being.ÔÇŁ

They were told the Youth Criminal Justice Act doesnÔÇÖt allow that. The act says courts ÔÇťshall not use custody as a substitute for appropriate child protection, mental health or other social measures.ÔÇŁ

In one court appearance, J.G. described Jade as an intelligent kid with a lot of potential, who, when sober, ÔÇťhas a lot of insight into her circumstances and life choices she makes.ÔÇŁ

J.G. said she had hope for Jade. ÔÇťI love her to death, to be honest,ÔÇŁ she said in court. ÔÇťSheÔÇÖs been dealt a difficult life and sheÔÇÖs just reacting to that.ÔÇŁ

In late March, Tim finally got some good news: Jade had been accepted into the secure treatment program at Syl Apps Youth Centre in Oakville. But even though she had met the criteria for admission, she remained on the waitlist. ÔÇťThere is (no) bed available right now,ÔÇŁ J.G. told him.

Jade ended up in the hospital again in April with bite marks on her face and chest. A 32-year-old man was charged with assault in what court records labelled as ÔÇťintimate partner violence.ÔÇŁ At 14, Jade was too young to consent to being intimate with an adult. Jade refused to give a statement or agree to a sexual assault examination, police records show. Crown prosecutors later withdrew the charge, citing no reasonable prospect of conviction.

JadeÔÇÖs child protection worker told Tim she was growing more concerned. Jade had tried to jump out of a moving vehicle while support workers were driving her back to her hotel. She was also telling people that she had ÔÇťbeen NarcanedÔÇŁ 17 times.

The CAS worker petitioned the court to have Jade taken to hospital for an involuntary psychiatric assessment. A judge agreed and signed the order, but when police brought Jade to the hospital, doctors said she didnÔÇÖt meet the criteria to be held. She was released.

To those who knew and loved her, Jade was a danger to herself, and drugs were her way of ending her life. But as J.G. wrote in an email to JadeÔÇÖs parents, drugs, ÔÇťwhile dangerous and can be fatalÔÇŁ are ÔÇťnot considered to be under the criteria of ÔÇśharm.ÔÇÖÔÇŁ

Jade turned 15 in yet another hotel, The Mount, a utilitarian guest house that was once a nunnery. ÔÇťMy birthday yay,ÔÇŁ she wrote in a TikTok video in which she showed off her new nails, painted black and gold. With dyed hair and dark eyeliner, she appeared much older than she was. She went missing later that day.

Jade called her father from jail one day in August. Tim was camping in Algonquin Park, on the trip they had planned together. The reception was bad and the call cut in and out.

Mona has saved her favourite pieces of Jade’s childhood art.

Star photoÔÇťYouÔÇÖre supposed┬áto be with me,ÔÇŁ Tim reminded her.

Jade cried. Tim had only just arrived at the campsite, but he packed up and drove home. At the detention centre, he found her in good spirits. She told her father that she was done with drugs and bad decisions.

ÔÇťI never want to go back that way again,ÔÇŁ she said.

Tim was hopeful. He told her, ÔÇťWeÔÇÖre all going to be there for you.ÔÇŁ

Jade should have been starting tenth grade in September 2024, during what would end up being the final weeks of her life. Instead, she was missing for much of the month. It had been a year since her birth mother left her in the lobby of the CAS office. A year of living in hotels.

Nicole and Jade had reconnected and Nicole was stunned by the change in her daughter. Jade was using dangerous street drugs and told Nicole she had watched a friend die in her arms from an overdose. Nicole was furious with CAS.

ÔÇťWhen I returned my daughter to you, she was skipping school and smoking weed,ÔÇŁ Nicole said she told JadeÔÇÖs child protection worker. ÔÇťNow sheÔÇÖs a full-blown drug addict.ÔÇŁ

CAS was no closer to finding an open secure treatment bed, J.G. told Tim in an email: ÔÇťHer behaviours, aggression and drug use are a significant barrier in getting her an appropriate placement.ÔÇŁ

In late September, J.G. met with lawyers and a youth court judge to discuss JadeÔÇÖs case in a Section 19 conference, an informal meeting meant to share concerns about young people in the criminal justice system.

ÔÇťAll agreed she needed secure treatment,ÔÇŁ the child protection worker wrote in an email to JadeÔÇÖs parents.

A court-ordered medical assessment had resulted in Jade being diagnosed with FASD ÔÇô more than a decade after her adoptive mother first flagged it as a possibility with doctors. (Nicole says she did not consume alcohol during her pregnancy and doesnÔÇÖt believe the diagnosis is accurate.) FASD is a serious developmental disability that impacts learning, attention, emotional regulation and impulse control. Early intervention can improve outcomes, but without it, risks include substance use, mental health issues and trouble with the law.

In early October, J.G. learned that Syl Apps finally had an available bed for Jade. The child protection worker filled out the paperwork immediately and an agency lawyer began working to schedule a court hearing.

J.G. shared the news with Tim, Mona and Nicole. She told them Jade could be in secure treatment within a month.

That same week, child protection workers visited NicoleÔÇÖs home as part of the pre-approval process to have Jade return to her birth mom after secure treatment, with more support this time.

ÔÇťAlthough cautious,ÔÇŁ J.G. wrote to the parents, ÔÇťvery hopeful.ÔÇŁ

Now they just had to find Jade. She hadnÔÇÖt been responding to TimÔÇÖs texts or calls for weeks. He worried he was losing her.

ÔÇťGod gave me a great gift when you became my daughter,ÔÇŁ he wrote to her in early October. He told her he was praying for her ÔÇťduring this most difficult time in your lifeÔÇŁ and said he believed in her.

ÔÇťYou can do it,ÔÇŁ he wrote. ÔÇťI KNOW THAT YOU CAN.ÔÇŁ

Tim was out with friends on Thanksgiving weekend when his roommate phoned to say the police were looking for him. It was three days after CAS learned about the secure treatment bed for Jade, but no one had seen her. Tim didnÔÇÖt need to hear the┬áofficer say the words. He knew right away that his daughter was dead. He had seen it coming. Everyone had.

A police officer drove Tim to the hospital to see Jade one last time. The coroner pulled down the white sheet covering her body. It was his girl. Her beautiful face. The hand sheÔÇÖd let him hold at Walmart the day they bought Moo-Moo. He leaned down and kissed her on the forehead.

Tim called Mona and Nicole to deliver the terrible news. Jade had overdosed on fentanyl. The 911 call had come from a rundown beige split-level on a residential street lined with compact houses. It was the home of a man in his 20s who Jade had described to family and friends as her boyfriend. Jade often ended up there when she ran away. (Reached at home, the manÔÇÖs mother said he did not want to be interviewed.)

Jade overdosed on fentanyl while at the home of a man in his 20s who Jade had described as her boyfriend. She was 15.

Steve Russell ╔ź╔ź└▓ StarAt JadeÔÇÖs funeral, Mona recalled how Jade loved watching ÔÇťFull House,ÔÇŁ eating popcorn with apple slices and drinking mocktail strawberry daiquiris at the swim-up bar on family trips to Jamaica. Mona broke down in tears and couldnÔÇÖt finish the eulogy.

Before Jade was cremated, her father had the funeral home tuck Moo-Moo into the coffin with her. Mona and Tim let Nicole take JadeÔÇÖs ashes home. Nicole placed them on a memorial table in what was once her daughterÔÇÖs bedroom. Tim kept a small vial of ashes that he plans to scatter in Algonquin Park this summer.

Nicole said a police officer told her that Jade got the fentanyl from someone outside a homeless shelter, but they werenÔÇÖt able to determine who. A London police spokesperson did not answer questions from the Star about the police investigation but said ÔÇťthe coroner did not find any criminality.ÔÇŁ

Eight months after JadeÔÇÖs death, none of the reviews that are meant to prevent future tragedies have happened.

A provincial committee called the Child and Youth Death Review and Analysis (CYDRA) unit investigates the deaths of children in CAS care and makes recommendations to prevent future harm. Within 21 days of a death, the committee is supposed to decide if CAS must undertake an internal review, a process outlined in a joint directive between the coronerÔÇÖs office and the ministry of children, community and social services. The ministry then directs CAS to conduct the review, which must be led by an independent expert and completed within roughly five months.

London CAS has not been instructed to launch a review, several sources told the Star. In a statement, the CAS said they canÔÇÖt comment on specific individuals, but confirmed they are not currently conducting any child death reviews.

A spokesperson for the┬ácoronerÔÇÖs office said they canÔÇÖt speak to individual cases, but noted that in practice, the 21-day timeline ÔÇťis not firm.ÔÇŁ The ministry website says that while the coronerÔÇÖs office ÔÇťstrives to meet the timelines for review decisions as outlined, there are a number of circumstances that impact and often delay this ability,ÔÇŁ including that autopsies and coronerÔÇÖs reports can take many months to complete.

Nicole keeps JadeÔÇÖs ashes on a memorial table in what once was JadeÔÇÖs bedroom.

Steve Russell ╔ź╔ź└▓ StarThe ministry of children, community and social services did not respond directly to questions from the Star, but sent a statement that said ÔÇťthe death of any child or youth is heartbreaking and deeply tragic,ÔÇŁ and listed recent government investments in the child welfare sector while highlighting a proposed bill they say will bring more oversight. The health ministry did not respond.

London CAS and other child welfare agencies continue to urge the province to create more residential care and treatment options. When questions about these long-standing challenges were put to Premier Doug Ford last fall, he countered by calling an audit of the child welfare system, alleging misuse of government dollars.

The Ontario Ombudsman is investigating the practice of children and teens being inappropriately housed in hotels, motels and offices. A report is expected later this year.

Weeks before she died, Jade told a judge she planned to go to college to study youth care. She said she wanted to help kids like her.

Tim believes his daughter could have turned things around and was denied the chance. ÔÇťThis isnÔÇÖt the life story she wanted,ÔÇŁ he said.

He keeps returning to the text message he sent Jade the week before she died, telling her he believed in her. Jade didnÔÇÖt reply, but the ÔÇťreadÔÇŁ receipt appeared under the message. It comforts him to know that she saw it.

ÔÇťUntil I see you again,ÔÇŁ he wrote, ÔÇťbe safe and I love you so much.ÔÇŁ

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation