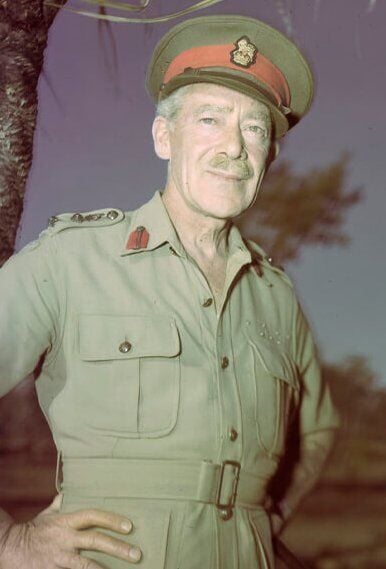

The Surrender of Japan 80 years ago on Sept. 2, 1945, aboard the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay marked the end of the Second World War. Canada’s representative for the signing of the Instrument of Surrender was Colonel Lawrence Moore Cosgrave, my great-grandfather.

Colonel Cosgrave’s role during the surrender has retained a place of interest in Canadian history, due to the uncertainty of why he signed on the incorrect line of the Japanese copy of the surrender documents. His minor error has led misinformed journalists and amateur historians to smear Cosgrave and attempt to create a fake outrage which is unfair and unjustified. For instance, writing in The Globe and Mail in 2015, Allan Richarz described Cosgrave as the official who nearly “.”

It is time for the historical record to be corrected.

Colonel Cosgrave’s lifetime of service for Canada began at the outbreak of the First World War, when he volunteered for the Canadian Expeditionary Force with his friend John McCrae, who he had met while both were attending McGill University. Cosgrave and McCrae remained close friends until McCrae’s death in 1918. Indeed, McCrae wrote “In Flanders Fields” on a piece of paper placed on Cosgrave’s back. With McCrae, Cosgrave fought at the and was later awarded the Croix de Guerre by the French government in addition to two Distinguished Service Orders for gallantry in action. After surviving the horrors of the war, Cosgrave served as a trade commissioner and diplomat during the interwar period. In 1942 he returned to military service, acting as the Canadian military attaché to Australia during the Second World War.

The “controversy” over Colonel Cosgrave’s signing error came during the Signing ceremony. When it was Canada’s turn to sign the Japanese copy of the Surrender, Cosgrave unintentionally signed one line too low, on the line designated for the French Republic. The mistake could be attributed to the fact that Colonel Cosgrave was blind in his left eye, stemming from an injury that occurred during the First World War. On the Allied copy of the document, Cosgrave signed on the correct line.

It was never Cosgrave’s military or diplomatic peers who made a public issue over the signing problem. U.S. General Richard Sutherland, Douglas MacArthur’s chief of staff, simply crossed out “French Republic” and wrote “Dominion of Canada” under Cosgrave’s signature and subsequently made similar corrections for the remainder of the document. Japan’s delegation accepted the corrected document. Rather, it was The New York Times reporter Robert Trumbull, in a special dispatch to The Globe and Mail, who wrote that the signing error “will rank high among the historic bobbles of our time.” It has been this inflated narrative that has dominated in the 80 years since the Surrender. Canadian journalists and historians have never made an effort to correct this unfair judgment. Historians are taught not to assign causation to people and events without sufficient evidence. This tenet has been neglected in Colonel Cosgrave’s case.

The real reason Cosgrave signed on the wrong line is most likely because he was blind in his left eye. Cosgrave first sustained an eye injury during a boxing match while he was a student at the Royal Military College, leading to significant vision loss. After being wounded while fighting on the Western Front in April 1917, Cosgrave lost full sight in that eye.

Cosgrave retired from the Canadian military in 1946 and resumed his work as a diplomat until 1955. In a letter to a diplomatic colleague following the war, Cosgrave wrote that his appointment to the Surrender ceremony would remain “the highlight of my not uneventful career.” In a career filled with highlights, Colonel Cosgrave’s place at the Surrender ceremony was well earned.Â

This tendency among Canadians to tear down our historical figures lessens the significant contributions Canadians have made in history. It weakens Canada’s story. If Canadians want to understand our place in the world 80 years after the Second World War, a deeper and more nuanced understanding of our national accomplishments is essential.

The burden to set the historical record straight in order to uphold the legacy of a Canadian war hero shouldn’t fall solely on family.

Error! Sorry, there was an error processing your request.

There was a problem with the recaptcha. Please try again.

You may unsubscribe at any time. By signing up, you agree to our and . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google and apply.

Want more of the latest from us? Sign up for more at our newsletter page.

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation