ÔÇťI donÔÇÖt want to imitate life in movies,ÔÇŁ Pedro Almod├│var once said. ÔÇťI want to represent it.ÔÇŁ

The tension between the way things look and seem and how they feel is at the heart of cinema, and few filmmakers have mined it as deeply as the Spanish writer-director, whose movies donÔÇÖt so much reject reality as renovate it according to a florid, colour-coded set of blueprints.

If itÔÇÖs possible for art to locate authenticity in artifice, Almod├│varÔÇÖs twisty, genre-hopping movies┬ádocument their makerÔÇÖs five-decade quest to unveil a series of carnal, cathartic truths about love, lust and other basic instincts. His work will be on display in Laws of Desire: The Films of Pedro Almod├│var,┬á, beginning Nov. 1 and running through December.

Pedro Almod├│var attends a screening of his latest film, “The Room Next Door,” on Oct. 20, 2024 in London, England.

Kate Green/Getty Images for Warner Bros. PicturesFor viewers familiar with Almod├│varÔÇÖs most famous movies ÔÇö the delectably accessible “All About My Mother” (1999) and “Talk to Her” (2002), both of which won Academy Awards ÔÇö the punky, transgressive sensibility of his formative work may come as a shock. His earliest features are still bracing, like slaps in the face from a velvet glove.

One way to look at a movie like 1982ÔÇÖs “Labyrinth of Passion” ÔÇö a raucous, polymorphously perverse romp about a sex-addicted pop star who becomes besotted with a Middle Eastern prince against a zany backdrop of orgies, punk shows and religious terrorism (screening Dec. 14) ÔÇö is as a kamikaze course correction away from the repression of the Franco years. If the dictatorÔÇÖs death in 1975 represented a shot in the arm for SpainÔÇÖs countercultural vanguard, Almod├│varÔÇÖs low-budget, high-concept provocations were tantamount to celluloid adrenalin.

The sensation of moviemaking in overdrive applies to much of Almod├│varÔÇÖs ‘80s output, which made him an international film-festival mainstay even as his work typically trashed bourgeois mores and morality while ostensibly working as crowd-pleasers.

The bloody bullfighting imagery of 1986ÔÇÖs “Matador” (Nov. 21) literalized the directorÔÇÖs desire to skewer sexual, cultural and cinematic taboos with extreme prejudice. As an aspiring toreador plagued by violent visions straight out of a ‘70s giallo thriller, the impossibly young Antonio Banderas made even crippling neurosis seem smouldering.

Banderas would continue to pop up at regular intervals in Almod├│varÔÇÖs filmography, serving as the starriest member of a rotating repertory mostly made up of superlative and emotive female performers. The filmmakerÔÇÖs fascination with women’s experiences ÔÇö especially stories exploring maternal devotion ÔÇö helped to make icons of actors like Julieta Serrano, Marisa Paredes, Rossy de Palma, Cecilia Roth and Carmen Maura. Another, Pen├ęlope Cruz, has consistently done her best work for her longtime friend, claiming that their collaboration ÔÇö which started in 1997 with “Live Flesh” ÔÇö is the byproduct of what she calls a ÔÇťsupernatural connection.ÔÇŁ

Any attempt to reduce Almod├│varÔÇÖs stylistically diverse and emotionally spacious filmography to a tidy set of themes and preoccupations is bound to come up short. Still TIFFÔÇÖs retrospective provides casual viewers and devotees alike with myriad opportunities to juxtapose major and minor works in search of telling resonances between them.

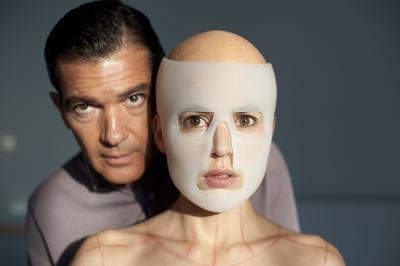

For instance, it would be fascinating to pair 1983ÔÇÖs scabrous, wilfully sacrilegious “Dark Habits” (Nov. 9) ÔÇö a delirious farce about a dysfunctional convent presided over by a drug-addicted Mother Superior ÔÇö with 2004’s “Bad Education” (Dec. 7), which takes a more measured and sinister tack in critiquing the Catholic Church, or to double-bill 1989’s “Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (Dec. 1) with 2011’s “The Skin I Live In” (Nov. 26), twin psychodramas about women being held hostage by obsessive male captors that limn the limits of Stockholm syndrome.

Gael Garcia Bernal stars in the Pedro Almod├│var crime drama “Bad Education.”

Sony Pictures ClassicsAlmod├│varÔÇÖs 2020 short “The Human Voice” (Nov. 8 and Dec. 17), starring Tilda Swinton, serves simultaneously as an adaptation of a stage monologue by the French Surrealist Jean Cocteau and a spiritual sequel to two of his greatest and most philosophically complex features: 1987’s “Law of Desire” (Dec. 21) and 1988’s “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown,” (Dec. 27), both of which integrate CocteauÔÇÖs play into their storylines.

The extent to which Almod├│varÔÇÖs 20-plus features tend to reflect and refract one another is why picking a single favourite from his oeuvre is such a daunting challenge.

That said, a case can be made that his most affecting and accomplished movie is also one of his most recent: 2019’s “Pain and Glory” (Dec. 5), which casts Banderas as a filmmaker modelled on Almod├│var himself ÔÇö right down to his heritage as a former libertine and countercultural warrior weighing the compromises (personal and artistic) of maturity.

The self-reflexive self-portrait-of-the-artist-as-a-flawed-visionary is a mainstay of capital-A Auteur cinema (think “8┬Ż” and the vast majority of Woody Allen), but “Pain and Glory” vibrates with humanity and humility. ItÔÇÖs less a victory lap around Almod├│varÔÇÖs career than a meditation on what happens when somebody who has dedicated themselves to imitating life is suddenly obliged to do a reality check.

The scene in which BanderasÔÇÖ Almod├│var stand-in tries to reignite an old flame, only to watch it flicker out before his eyes, is one of the great pieces of contemporary screen acting. Among other things, it proves that a filmmaker who became beloved for his willingness to take his ideas, his actors and his audiences spiralling over the top is able to practice his mastery in miniature.

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation