Had he single-mindedly pursued a career as a goaltender and retired into obscurity, Ken Dryden would have been heartily eulogized around the hockey-loving world in the wake of his death on Friday at age 78 after a battle with cancer.

DrydenÔÇÖs NHL career was as short as it was shockingly flawless. In a little more than seven seasons as the starting goaltender for the Montreal Canadiens, he won six Stanley Cups and five Vezina trophies as the leagueÔÇÖs top netminder. Thrust into the CanadiensÔÇÖ crease in the 1971 playoffs after playing just six regular-season games in the wake of a short minor-league apprenticeship, his backstopping of an underdog team to a championship and sustained excellence thereafter made him the only player in hockey history to win the Conn Smythe Trophy as playoff MVP before winning the Calder as rookie of the year. Not long after that, Dryden was in net for Canada when Paul Henderson scored the epochal goal to beat the Soviet Union in the 1972 Summit Series.

He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1983. He saw his number 29 retired by the Canadiens in 2007. All of it was more than enough to qualify as an athletic life well lived. Which is why DrydenÔÇÖs signature pose┬áÔÇö his masked figure slouched in the crease, chin resting on gloves draped over the knob of his goal stick┬áÔÇö has long been immortalized in a bigger-than-life bronze statue that greets visitors to the Yonge Street shrine.

But Dryden wasnÔÇÖt only a great Canadien. Thanks to a sprawling post-playing career, he was also a great Canadian. At various times an author, teacher, lawyer and federal cabinet minister, Dryden was also team president of the Maple Leafs the last two times they ventured beyond the second round of the playoffs, in 1999 and 2002. He wasnÔÇÖt just the man who gave us ÔÇťThe Game,ÔÇŁ widely regarded as the greatest hockey book and one of the best sports books ever written. He was in many ways the conscience of a mostly shameless sport, a staunch advocate for prioritizing skill over the thuggery that sometimes prevailed in his playing prime, and a vocal critic of the NHLÔÇÖs denial of the link between brain injuries and CTE.

Dryden wasnÔÇÖt just a legend of the game, he was the consummate student of it, and its need for evolution.

ÔÇťFew Canadians have given more, or stood taller, for our country,ÔÇŁ Prime Minister Mark Carney said in a statement. ÔÇťKen Dryden was Big Canada. And he was Best Canada. Rest in peace.ÔÇŁ

Though Dryden rose to fame as a linchpin of the Scotty Bowman-coached Montreal team that dominated the NHL of the 1970s, the bespectacled six-foot-four goaltender was, for most of his life, a ╔ź╔ź└▓nian. Born in Hamilton in 1947, he grew up in Etobicoke, where he starred on local baseball diamonds and on the basketball court at Etobicoke Collegiate.

But it was in a hockey net that he emerged as a professional commodity. Drafted 14th by the Boston Bruins in 1964, the story goes he was traded to the Canadiens after he made known his relatively unconventional decision to attend university before turning pro, studying history at Cornell University while leading the Big Red to the 1967 NCAA championship.

As Montreal hockey columnist Red Fisher once wrote: “Dryden was different. This was one goaltender who danced to his own tune.”

Dryden was at his best when it mattered most, going a stunning 80-32 in the playoffs. He certainly played the game on his own terms. In 1973-74, as the reigning Vezina winner and a two-time Stanley Cup champion at the peak of his powers at age 26, he announced his retirement and sat out an entire season in a contractual dispute with the Canadiens. This was around the time the upstart World Hockey Association was reconstructing pro hockeyÔÇÖs pay scale. Dryden made the case to Canadiens general manager Sam Pollock that his $80,000 salary wasnÔÇÖt commensurate with market comparables. It wasnÔÇÖt simply about the size of the paycheque, Dryden argued. It was a matter of principle.

ÔÇťThe actual amount of money you make hasnÔÇÖt much to do with making you happy,ÔÇŁ he told reporters at the time. ÔÇťIf you see the guy next to you doing the same work you do getting twice as much, youÔÇÖre unhappy, naturally. ItÔÇÖs not fair.ÔÇŁ

To make his point he spent that season articling at a ╔ź╔ź└▓ law firm┬áÔÇö heÔÇÖd gone to law school at MontrealÔÇÖs McGill University while playing for the Canadiens┬áÔÇö taking the subway to an office near King and Yonge, where he was paid the princely sum of $134 a week. Dryden supplemented that income by doing colour commentary for the WHAÔÇÖs ╔ź╔ź└▓ Toros while reports swirled he might defect to the rebel league. But after the Canadiens lost in the first round of the playoffs without the services of their No. 1 netminder, the team convinced Dryden to sign a three-year contract worth a reported $200,000 a year.

Four more Stanley Cups followed before Dryden, in the summer of 1979, made another retirement announcement, this one for good. Freed of the season-long grind, he passed the bar admission course. He travelled Europe. In 1983, he published ÔÇťThe GameÔÇŁ to glowing reviews and blockbuster sales. It was the first of his small library of books.

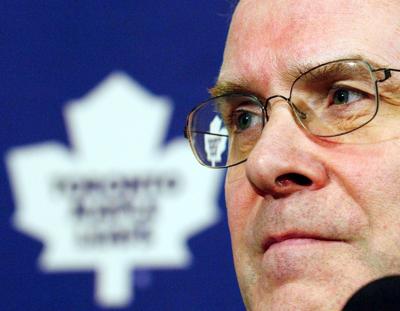

By 1997, he was ready to return to the NHL at the helm of the Leafs. It was a moment of tumult in Leafland. Around the time the team was moving from Maple Leaf Gardens into whatÔÇÖs now known as Scotiabank Arena, one of DrydenÔÇÖs earliest tasks involved stewarding the franchise through the abuse scandal that saw a former Gardens usher convicted of sexually assaulting boys. Dryden met that moment with all the humility and decency it required.

During his tenure in ╔ź╔ź└▓, front-office infighting was a central theme, and Dryden was more than once accused of dithering. Seen through the lens of recent history, mind you, the results were stupendous. And there was never a doubt that Dryden understood the tortured plight of the Leafs fan.

ÔÇťIt is easy to say that a fan can stay home,ÔÇŁ Dryden wrote in ÔÇťThe Game.ÔÇŁ ÔÇťBut itÔÇÖs not as simple as that. A sports fan loves his sport. A fan in ╔ź╔ź└▓ loves hockey, and if the Leafs are bad he loses something he loves and has no way to replace it.ÔÇŁ

In a sports conversation built on clich├ę-riddled sound bites, Dryden spoke in well-considered sentences and paragraphs that verged on soliloquies. Once, when a New York Times reporter was a passenger in DrydenÔÇÖs black Saab on a trip from Buffalo to ╔ź╔ź└▓ in the lead-up to the 1999 conference final between the Sabres and Leafs, the reporter measured one of DrydenÔÇÖs answers by the carÔÇÖs odometer. It clocked in around 10 kilometres. A deep thinker in an often thoughtless sport, Montreal’s No. 29 was one of one.

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation