Just up the road from the É«É«À² Zoo sit an unassuming smattering of industrial buildings. But within its walls and under its floors lie a stinky secret.

This facilityÌý— the Zooshare Biogas PlantÌý— is the final resting place for some 15,000 tonnes of inedible food waste each year, collected from grocery stores, restaurants and shopping malls across the city.

“This is stuff like rotten food that is not safe for human consumption,”Ìýsaid Rob Grand, general manager of ZooShare Biogas Co-operative Inc., the non-profit that runs the plant. “It’s stuff that normally would just sit in a landfill and produce methane. We’re harnessing that to produce electricity.”

A report from Second Harvest details how much food that could be used to feed people is instead being wasted.

A report from Second Harvest details how much food that could be used to feed people is instead being wasted.

For 24 hours a day, seven days a week, the plant’s churning mechanisms turn food scraps and fryer oil into renewable power. It’s responsible for flooding Ontario’s power grid with 4.1 million kilowatt-hours of electricity every yearÌý— enough to power 250 homes.

With being wasted, including more than $58 billion in preventable losses every year, it’s unlikely the facility will ever run out of resources.

Zooshare offered the Star a sneak peek inside its smelly operations. Here’s how it works.

Off to a crappy start

In the beginning, there was poop.

Before the Zooshare plant opened in 2021, its grounds were used to store copious amounts of animal feces from the É«É«À² Zoo. Looking at the fields of spread-out poop, zoo bigwigs had one thing on their minds: “How can we monetize this animal manure?” Grand said.

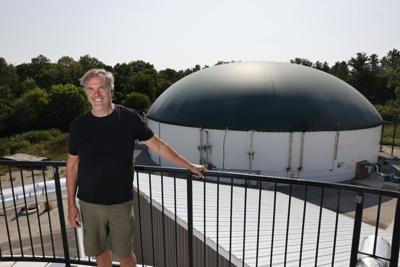

Rob Grand, General Manager of ZooShare Biogas Co-operative Inc., takes the Star on a tour of their facility where food waste is being used to generate electricity in É«É«À².

Lance McMillanThe answer seemed simple. They would take this poop, mix it with inedible food scraps and digest it all in a big vat into valuable biogas. It would provide a source of renewable energy, solve the zoo’s poop problem and earn a few bucks on the side.

With that mission statement, the Zooshare Biogas Plant began. And it almost immediately ran into a problem.

The plant just wasn’t designed to process manure, despite it being a main impetus behind its creation, Grand explained. The sticks, rocks, straw and other contaminants would get gunked up in the machinery, damaging the systems and wasting precious time.Ìý

In 2023, the plant operators finally decided to cut the crap and settle for processing pure food waste.

The facility is still used to store the zoo’s animal manure before it gets shipped off for processing into fertilizer. But without the poop being directly digested into biogas, the plant has at least become far less stinky, Grand said.

Off the plate and into your power outlet

Zooshare takes in inedible food scraps, used cooking oil and the gunk from grease traps from businesses all over the city. A good portion comes from grocers like Loblaw stores, which provided someÌý668,000Ìýkilograms of food waste from itsÌýÉ«É«À²-area locations in 2024, a Loblaw spokesperson told the Star.

BuildingÌýbigger, cleaner, smarterÌýelectricity systems should be the top priority of the federal government’s promise to build projects that are in

BuildingÌýbigger, cleaner, smarterÌýelectricity systems should be the top priority of the federal government’s promise to build projects that are in

All this organic matter gets blitzed into a pulp before it’s loaded into massive tanker trucks and shipped to the facility, Grand explained. To reduce the smell, this slurry is loaded into two massive, underground receiving tanks capable of holding 150,000 litres of sludge each.

We watched as a massive truck capable of holding up to about 25,000 litres of grease trap waste deposited its load into the underground tanks. As the heavy lid to the container opened, we were buffeted by the unholy and sickly sweet aroma of rancid oil and rotten food of a thousand varieties.

“You get used to the smell,” the trucker laughed as we instinctively gagged.

If not for the plant, all this food and oil waste would be destined for the landfill, where it would decompose into harmful methane, carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, Grand explained. By capturing these gases and turning them into electricity, the plant reduces some 20,000 tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions every year.

A gassy digestion process

From the receiving tanks, the biopulp gets pumped into massive pasteurization tanks where the slurry is heated to 70 C for about an hour to kill off harmful microbes. The sludge is then cooled before entering the digesterÌý— a building-sized “artificial stomach” where, over the course of the next 20 to 40 days, the foul biopulp is slowly broken down to release biogas.

A worker facilitates the deposit of grease trap waste into one of the receiving tanks at the ZooShare Biogas Co-operative site where food waste is being used to generate electricity in É«É«À².

Lance McMillan/É«É«À² StarInside, contaminants like plastic or cardboard that sink or float to the top of the tank are removed by sweepers at the bottom or skimmers at the top, said Grand. He’s seen all sorts of surprising contaminants, including a mangled stuffed animal from the zoo.

The plant’s automated processes allow it to run almost constantly. Unlike other renewable energy sources like wind and solar, biogas is able to run at capacity 24/7, without being bound to the whims of the weather and environment, Grand explained. All it needs is sufficient food.

When the slurry is all digested out, the gaseous and liquid contents of the two-million-litre digester are pumped into a massive domed building for storage. The leftover goop gets shipped off as nutrient-rich fertilizer to farms across Ontario, while the gas is pumped into a generator on-site where it’s burned to make electricity.

This generator is “basically a 12-cylinder engine,” Grand said. “The biogas comes in and it’s the fuel that’s ignited to produce electricity... the heat from the engine is then used to heat up the pasteurization tanks.”

Finally, the electricity is fed straight into Ontario’s power grid, helping hundreds of homes keep the lights on across the province.

“It’s a beautiful circular model,” Grand said. “The fields of local farms get fertilizer. They grow food, it goes to market, food waste comes back to us, we produce electricity and then we ship the other byproduct, the fertilizer, to local farms.”

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation